Valuation is one of those four-syllable business buzzwords you’re going to have to deal with, eventually, if you either want to start a business or own a business. If it doesn’t come up when you start, it will come up later. Here is what I think you need to know, in five short points.

- The word has vastly Different meanings: don’t you hate it when the same words mean different things? Valuation means at least three different things:

- What a business is worth to accountants for legal purposes, such as divorce settlements, inheritance taxes, and gift taxes. A certified valuation professional, usually a CPA, makes a guess. Most of them use financial statements and analyze financial details.

- What a business is worth to a buyer. Small businesses go up for sale with business brokers. Hardware stores, for example, get about 40-50% of annual sales plus inventory, as a starting point. Plus a bonus for growth and special strengths, or a discount for lack of growth and special problems.

- The pivot point in an investment proposal: it’s simple math, but tough negotiations. If you say you want to get $1 million for 50% of your company, you just proposed a valuation of $2 million.

- What’s anything worth? Like your car, your house, and a share of IBM stock, something’s worth what somebody will pay for it. The valuation in A is theoretical, hypothetical, but legal. With B and C, though, valuation is as real as agreeing to buy a house. It’s not what the seller says it is; it’s what the buyer is willing to pay. And this cold hard fact drives many entrepreneurs crazy.

- For Small businesses, there are guidelines and rules of thumb. If you do a good search, or work with a business broker, you can find general rules of thumb for what your long-standing small business is worth. For example, a hardware story is worth roughly half a year’s sales plus inventory, with bonuses for positive factors like recent growth, and discounts for negatives like lack of growth. You could read up on it in bizbuysell.com, bizequity.com, or business brokerage press. Or do a web search and check the ads for valuation experts.

- For Startups, it’s what founders and investors negotiate. Startups and investors and culture clash over valuation. Investors care about valuation. Founders often misunderstand valuation. And never the twain shall meet. I’ve seen these kinds of problems many times: Founders walk into the valuation discussion full of folklore and fantasy like stories of Facebook and Twitter. They want lots of money for very little ownership. Investors see two or three people with no sales history thinking their dream startup is already worth $2 or $3 million.

- Irony: sometimes traction, and revenues, make things worse. It’s easier to buy the dream than the reality. The same investors who’ll seriously consider a $2 million valuation for a good idea, business plan, and a credible 3-person management team – but with no sales ever — might just as easily balk at a valuation of $600,000 for a company with three years history, 20% growth, and annual sales of $300,000. Despite the irony, it makes sense: few existing businesses are worth more than a multiple of revenues, but, still, before the battle, it’s easier to dream big. Or so it seems. I’ve been on both sides of this table, and I don’t have any easy solutions to offer.

If it hasn’t come up yet, it will. Every business deals with valuation eventually. The place any business sees it is during the early investment phases; but most businesses don’t get investment, so they can ignore it at that point. But then if it survives, or grows, valuation comes up again, because even if the business is immortal, the people aren’t: so eventually you either sell it or pass it on to a new team, an acquiring company, or your own family. And there’s the divorce and estate planning elements that require valuation. So every entrepreneur and business owner should have some idea what it is.

(Image: courtesy of wordle.net)

Looking for Investment? Understand Startup Valuation

How much equity do I have to give to angel investors? If you’re a startup founder looking for angel investment, you need to understand valuation. It’s a buzzword that people use in other contexts, too, which adds to the confusion. But it’s ultimately what determines how much of your company your investors will get, and how much you keep, if you manage to land an angel investment deal. So it’s a critical question that comes up a lot.

Equity means ownership. So 25% equity is 25% of the ownership of the business. Usually that’s a matter of shares. The math is fairly simple, but important: Logically, if an investor gives you $250,000, on a valuation of $500,000, that means half your company. The investor owns half, you own half. If the investor gives you the same $250,000 on a valuation of $1 million, then that means the investor gets 25%, you keep 75%. (Technically that’s what they call pre-money valuation, and there is also post-money valuation, but I’m not going to deal with that here. You get the point.)

Startup valuation in practice

What I’ve seen in practice, in nine years of membership in an angel investment group, is that valuation is an agreed-upon guess. There are no formulas commonly accepted formulas (although there are some formulas, such as you’ll see in this post from the angel capital association; it’s just that I rarely see them used in practice). In my experience, what really happens is all about saying no. Investors say no to valuations that are too high, startup founders say no to startup valuations that are too low. When the startup needs $250,000, the founders are rarely going to accept valuations of less than $1 million, because they need to maintain substantial ownership. When investors aren’t comfortable with valuations that high, they most often simply pass on the investment. I don’t see discussions in detail of components of valuation, like one sees in home buying transactions when buyer and seller go into details of square footage and comparable deals in the neighborhood.

Angel investment deals often postpone valuation by using convertible notes. The note is debt, supposedly to be paid off; but convertible means both sides intend to convert that debt to equity shares later, so that it should never be paid off, just converted to shares. In that case, angels are saying essentially, “we believe in you enough to give you this money, but we’re not sure of your valuation, so we’ll postpone that for later.” What both sides want is a follow-on investment, they hope for more money, from venture capitalists, to set the valuation later.

Five things you need to know about valuations

- The word has vastly Different meanings: don’t you hate it when the same words mean different things? Valuation means at least three different things:

- What a business is worth to accountants for legal purposes, such as divorce settlements, inheritance taxes, and gift taxes. A certified valuation professional, usually a CPA, makes a guess. Most of them use financial statements and analyze financial details.

- What a business is worth to a buyer. Small businesses go up for sale with business brokers. Hardware stores, for example, get about 40-50% of annual sales plus inventory, as a starting point. Plus a bonus for growth and special strengths, or a discount for lack of growth and special problems.

- The pivot point in an investment proposal: it’s simple math, but tough negotiations. If you say you want to get $1 million for 50% of your company, you just proposed a valuation of $2 million.

- What’s anything worth? Like your car, your house, and a share of IBM stock, something’s worth what somebody will pay for it. The valuation in A is theoretical, hypothetical, but legal. With B and C, though, valuation is as real as agreeing to buy a house. It’s not what the seller says it is; it’s what the buyer is willing to pay. And this cold hard fact drives many entrepreneurs crazy.

- For Small businesses, there are guidelines and rules of thumb. If you do a good search, or work with a business broker, you can find general rules of thumb for what your long-standing small business is worth. For example, a hardware story is worth roughly half a year’s sales plus inventory, with bonuses for positive factors like recent growth, and discounts for negatives like lack of growth.

- For Startups, it’s what founders and investors negotiate. Startups and investors and culture clash over valuation. Investors care about valuation. Founders often misunderstand valuation. And never the twain shall meet. I’ve seen these kinds of problems many times: Founders walk into the valuation discussion full of folklore and fantasy like stories of Facebook and Twitter. They want lots of money for very little ownership. Investors see two or three people with no sales history thinking their dream startup is already worth $2 or $3 million.

- Irony: sometimes traction, and revenues, make things worse. It’s easier to buy the dream than the reality. The same investors who’ll seriously consider a $2 million valuation for a good idea, business plan, and a credible 3-person management team – but with no sales ever — might just as easily balk at a valuation of $600,000 for a company with three years history, 20% growth, and annual sales of $300,000. Despite the irony, it makes sense: few existing businesses are worth more than a multiple of revenues, but, still, before the battle, it’s easier to dream big. Or so it seems. I’ve been on both sides of this table, and I don’t have any easy solutions to offer.

If it hasn’t come up yet, it will. Every business deals with valuation eventually. The place any business sees it is during the early investment phases; but most businesses don’t get investment, so they can ignore it at that point. But then if it survives, or grows, valuation comes up again, because even if the business is immortal, the people aren’t: so eventually you either sell it or pass it on to a new team, an acquiring company, or your own family. And there’s the divorce and estate planning elements that require valuation. So every entrepreneur and business owner should have some idea what it is.

(Image: courtesy of wordle.net)

True Story: Dollars vs. Eyeballs in Business Valuation

It was a warm late-spring day in 1999. I sat in my office with a venture capitalist, my lawyer, and my son.  The sun beamed in the patio outside my office. We talked about Palo Alto Software and its web subsidiary bplans.com. At one point the VC said:

The sun beamed in the patio outside my office. We talked about Palo Alto Software and its web subsidiary bplans.com. At one point the VC said:

You wouldn’t be an attractive investment for VCs. You’re too profitable.

I chuckled. I thought it was a joke. We’d grown sales in four years from less than $1 million to more than $5 million annual sales. We had to be profitable because we had no outside money.

He said:

That’s no joke. It’s like the Oklahoma gold rush, a land grab, and the assumption is that if you’re profitable, you’ve stopped too soon. You should be spending more to build traffic.

Those were strange times.

(Image: iDesign/Shutterstock)

BizEquity Adds Tools for Estimating Valuation

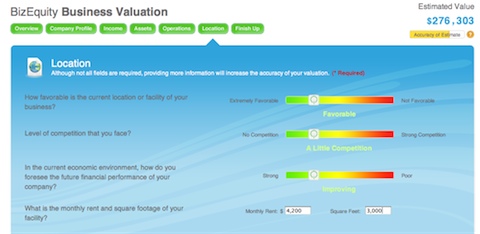

I’ve posted here before on BizEquity, the “Zillow of small business valuation” site offering quick estimates of business valuation.

BizEquity founder Tom Taulli — a true expert in the field — has added some interesting new tools for the site. Most notably, a valuation wizard that can take your inputs and give you a quick and dirty estimate of what your business is worth.

I did a test run over the weekend, by inventing hypothetical numbers for an Internet company. I had it started just three years ago, growing sales to $350,000. It had little or no profits, a bit of debt, and a lot of dependence on the owner (the site’s auto wizard asked me the right questions). The estimate ended up at about $275,000, with interesting variations above and below that depending on how I set several sliders. You probably can’t read the details in the shrunken illustration below, but the sliders are asking how favorable the location is, the level of competition, and how you foresee the future financial performance.

With the way the sliders work, you can see instantly how valuation would change with different settings.

Obviously, these are just estimates. As with estimates of house values, before you list your house, these estimates give you some idea, but are far from exact. They’re based on some standard formulas that estimate valuation using factors like sales, profits, assets, liabilities, and so forth. Don’t even dream of using this for a tax-related valuation, which requires a certified valuation professional; but it’s still a useful first look.

Valuation Questions, Web 2.0, Real World

I think valuation is fascinating. What is a company worth? With the larger publicly traded companies you can easily calculate a valuation using the wisdom of the crowd, the market itself, by multiplying shares outstanding times price per share. But in the real world of small business, gulp, this is much harder.

Concretely: how much is your business worth? How much could you sell it for? How would you decide? What formulas would you use? More importantly, what formulas would your hypothetical or theoretical buyers use?

Ultimately, like it or not, just about anything is worth what somebody else will pay for it. Your business is worth what you could sell it for.

And what would that be? Well, that’s really hard to know, until you go to the market. Some people talk about 5 or 10 or more times profits, but then face it, in small business, in the real world, profits is a very vague number, an accounting conceit. Some people talk about 1 or 2 or more times sales, which eliminates a lot of the accounting fiction. Others talk about valuations based on book value, or assets.

I’m amused at how much of this stuff is loosey-goosey, even though it’s in the realm of finance, which is supposed to be mathematical and exact. And isn’t.

I posted here last Fall about BizEquity.com, Tom Taulli’s really intriguing site that’s attempting to create a database of first-cut estimated valuations of businesses all over the United States. I talked to Tom last month after the big meltdown, and found, happily, he’s still optimistic about the long-term value of the BizEquity site. They’re working on it. I suggested he take his September data and multiply it by about 0.5 or so; and I was only partially joking. Tom knows this area very well, but of course the whole volatility burst has been a challenge. Last summer might not have been the most opportune time for Tom and his backers to start.

So I was interested yesterday Monday morning as I soaked in coffee and I noted — thanks to Ann Handley in Twitter — Advertising Age‘s Simon Dumenco’s angry analysis of the Huffington Post’s recent venture capital infusion at a valuation of $100 million.

His title, unfortunately, is What’s $200 Million Divided by 2009 Reality. That’s too bad, because the $100 million (or less) estimated valuation was widely publicized when Oak Investment Partners announced the investment last November. Simon doesn’t enhance his argument by referring to the twice-as-large-as-fact figure, $200 million, that actually appeared much earlier, last Spring. The phrase “straw man” comes to mind.

That glaring error aside, he seems offended by the VC’s reported valuation. He has references to the big Internet bubble of the late 1990s. It should be only $2 million, according to him.

I think he exaggerates his point, not just by doubling the figure, but also by lowballing his real estimate. The Huffington Post has made huge (and well reported) gains in traffic. Furthermore, unlike a lot of the Web 2.0 sites he wants to knock, this one has an actual revenue model. For better or worse, the Huffington Post is almost like old-fashioned media. It generates readers with news and opinion, and it sells advertising. So somewhere in the numbers — which are not public — is a number for revenues, and a valuation based on (among other things) revenues as well as traffic.

And it all goes to illustrate my point, today: valuation is hard to figure. It’s also important. And, in the end, a company is worth what buyers will pay for it. In the case of Huffington Post, it’s not a vague theoretical guess. The VCs who invested in Huffington set a price, and, with that, a valuation.

When You Need Valuation Numbers

The best readily-available valuation of business consulting services is 1.12 times annual sales. For automotive repair shops, it’s .41 times annual sales. Physical fitness facilities are going for .66 times gross annual profit. Grocery stores are going for .28 times annual sales, and sporting goods stores for .34 times annual sales.

There’s a valuation report in Inc Magazine’s April issue that turned me on to Business Valuation Resources, which sells information like the above, culled from data on actual transactions. I registered (free) to get a free download of a complex chart — sophisticated, innovative, imaginative, but really hard to read. And I gather that the underlying data isn’t cheap, because I can’t find anywhere to send you for a link to the data table, industry by industry, that I used to do the snippets in my first paragraph.

Conclusion: if you’re dealing with valuation, this could be a good resource. Valuation information is something like insurance account numbers: you don’t need it very often, but when you need it, you really need it. Like when you want to sell your company, or sell part of your company, or predict valuation as part of an investment negotiation, or when there’s a divorce, and … well, you get it.

Gripe: once they’ve published the data and put it out into the world as hard copy, can I get it online somewhere? Oh yeah, I get it, there’s value to the data. Tough call for BVR, how much do you give away to promote your data?

10 Rules for Valuation

(Note: I posted this on Up and Running yesterday. I’m crossposting it here for reader’s convenience. – Tim)

I really don’t like the word “valuation”; it sounds too much like an MBA buzzword. But I like even less the general confusion about the concept. We talk about starting businesses, we talk about running businesses, getting investment, getting financed, and we should take discussion of valuation for granted. Valuation is at the same time frequently necessary, obvious and extremely arcane. It is nothing more than what a company is worth. It becomes necessary more often than you’d realize, with buy-sell agreements and tax implications after death and divorce, plus financing and investment. It’s obvious because a business is worth what a buyer will pay for it. And then it breaks down into complex formulas and negotiations.

So here are 10 (I hope simple) rules for valuation.

- Valuation is what a company is worth. It’s like what a house or a car is worth–less than the seller says, more than the buyer says.

- A company’s ownership is almost always divided into shares. Let’s say your company has 100 shares, 51 yours and 49 your co-owner’s.

- Valuation equals shares outstanding times the price of one share. If the company is worth $500,000 and there are 100 shares, then each share is worth $5,000. (OK, there are exceptions, preferred shares and such, but leave the fine tuning for later.)

- Tax authorities say the price of a share is whatever it was at the last transaction. (There, too, there are exceptions, but let’s keep this simple.)

- When startups offer shares–equity–to investors, then that, too, is simple math. If you sell 20 percent of the company for $100,000, that means the company is worth $500,000.

- Investment deals frequently revolve around valuation. When investors question your valuation, they’re saying they want more ownership for their money, or want to invest less money for their ownership.

- Analysts often apply formulas. The most common formula is called “times profits” because it multiplies profits times some number. Another common formula is “times sales.” Companies might be worth two times sales or 10 times profits. There’s also book value, which is assets less liabilities. And there’s the estimated sale value of assets.

- Privately held companies are worth less than publicly traded companies. They get discounted for the disadvantage of not being able to convert ownership to cash easily.

- Growing companies are worth more than stable or declining companies.

- As with real estate, comparable sales matter. Analysts look for recent transactions involving similar businesses.

10 Good Reasons Not to Seek Investors For Your Startup

Before you buy into the myths about startup investors, first consider whether you actually want startup investors for your new business at all. No, I’m not bitter … I had VC money in Palo Alto Software for a few years and they were helpful, collaborative, and good people. I’m not a bitter victim. And I’ve invested in more than a dozen startups, so I don’t hate investors; I am one. But I try to tell the truth. Most businesses are better off without startup investors.

Before you buy into the myths about startup investors, first consider whether you actually want startup investors for your new business at all. No, I’m not bitter … I had VC money in Palo Alto Software for a few years and they were helpful, collaborative, and good people. I’m not a bitter victim. And I’ve invested in more than a dozen startups, so I don’t hate investors; I am one. But I try to tell the truth. Most businesses are better off without startup investors.

Bootstrapping is underrated

Which would you rather — steer by committee, with people looking over your shoulder? Or just do it yourself, you drive, you decide?

Also, before I go too far, yes, there are opportunities that demand investment. These are the opportunities that you can only address with substantial deficit spending, which are also worth it, with a big pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. If that’s what you’re looking at, hooray.

I’ve said it before: bootstrapping is underrated. I get frequent emails from people asking how they can get investment for their new startup, and I’ve admitted to being a member of an angel investor group. But let’s not forget, while we’re thinking about it, these 10 good reasons not to seek investors for your startup.

Startup investors are partners, co-owners, and sometimes bosses

- After investment, it’s not really yours anymore. That dream you had of building your own business ends when you take on outside startup investors. You have partners now. You have people who have a claim to ownership, shares, and having a voice in key decisions. You no longer set your own goals, strategy, milestones, and pace. You’ve got a share in a business, but not your own business. Investors write checks to own a serious portion of your business. I admit that’s patently obvious, but you should see the emails I get in which people think of investors as if they were some sort of public agency.

- Investors aren’t generic. Some become collaborative partners and even mentors, some are nagging insensitive critics. Some are trojan horses. Some help, some don’t. (Hint: choose carefully which investors you approach.)

- Investors can be bosses. You are not your own person when you have investors; you’re part of a team. You can’t decide everything by yourself. Politics matter. Investor relations matter. If you screw up, you do it in front of other people, and it hurts those people.

- Just getting financed doesn’t mean diddly. For an example of what I mean read this piece from the New York Times. You haven’t won the race when you get that check.

- Investors sometimes take your company from you. Well-known strategy consultant Sramana Mitra has a couple of eloquent minutes on that them in this two-minute video. She seems to be talking about India, but she’s well known in the Silicon Valley, and what she says applies perfectly well here.

- Valuation is critical to them and you. Simply put, valuation means the price. If you want to give only 10 percent of your company to investors who pay $100,000, you’re saying your company is worth $1 million. And so on. Simple math, but wow, not so simple negotiation.

- Investors don’t make money until there’s a liquidity event. That’s why we always talk about exit strategies. You can be the world’s happiest, healthiest, most cash-independent company, but your investors won’t be happy until you get them cash back. The win is getting money back out of the company. Some big company stock buyers like dividends. Startup investors don’t.

Besides which, startup investors are hard to land

- It’s almost impossible to get investment for your very first startup. If you don’t have startup experience, get somebody on your team who does. Chris Dixon said it best: either you’ve started a company or you haven’t. And if you haven’t, and nobody in your team has either, that makes it very hard.

- If it’s not scalable, forget it. The real growth opportunities are scalable. It used to be products only, but now there are some scalable services, like web services, for example. But if doubling your sales means doubling your headcount (that’s called a body shop), then investors aren’t going to be interested.

- If it’s not defensible, it’s tough going at best. Not that I trust patents as a defense, but trade secrets, momentum, a combination of trade secrets and patents, plus a good intellectual property defense budget … if anybody can do it, then investors aren’t interested. (Of course, what would I know, I thought Starbucks was a bad idea because I thought that was too easy to copy … there are always exceptions.)

20 Reasons to Write a Business Plan

Question: What are some of the main arguments for writing a business plan?

Question: What are some of the main arguments for writing a business plan?

Here are 20 good reasons to write a business plan. Please note, however, that a business plan is not necessarily a traditional formal business plan. It ought to be a lean business plan that gets reviewed and revised often. It ought not to be static, used once, and then forgotten.

These apply to all businesses, startup or not:

Key elements of a lean business plan

- Manage the money. Plan and manage cash flow. Will you need working capital to finance inventory purchase, or waiting for business customers to pay? To service debt, or buy assets? To finance the deficit spending that generates growth? Are sales enough to cover costs and expenses? That’s planning.

- Break larger uncertainties into meaningful parts. Go from big vague objectives to specific numbers, lists, and tables. It’s compatible with the way most humans think. A plan makes it easier to estimate and visualize needs, possibilities, and so forth

- Set strategy. Strategy is focus. It’s what you concentrate on, and why. It’s who is in your market, and who isn’t; and why and why not. It’s what you sell, to whom. You need to set it and then refer back to it, frequently, as things change. You can’t revise something you don’t have.

- Set tactics to align with strategy. Tactics like pricing, messaging, distribution, marketing, promotion have to work and they have to align with strategy. You can’t manage a high-end strategy with low-end pricing.

- Set major milestones. Concretely, what is supposed to happen, when? who is responsible? Humans work better towards specific milestones than they do moving in general directions. New product launch, website, new versions, new hires. Put it into milestones.

- Establish meaningful metrics. Of course that includes money in sales, spending, and capital needed. But useful metrics might also include traffic, conversion rates, cost of customer acquisition, lifetime customer value, or calls, emails, ads, trips, updates, hires, even likes, follows, and retweet. Good planning includes methods to track.

Dealing with business decisions

- Set specific objectives for managers. People work better with specific objectives, especially when the come within a process that includes tracking and following up. The business plan is the perfect tool for making this happen. Don’t settle for having it in your head. Organize and plan better, and communicate the priorities better.

- Share your strategy selectively. Let other people involved with your business know what you’re trying to do. Share portions of your plan with key team leaders, partners, spouse, bankers, allies. Don’t you want them to know.

- Deal with displacement. You have to choose, in business; particularly in small business; because of displacement “Whatever you do is something else you don’t do.” Displacement lives at the heart of all small-business strategy.

- Decisions on space and locations. Rent is a new obligation, usually a fixed cost. Do your growth prospects and plans justify taking on this increased fixed cost? Shouldn’t that be in your business plan?

- Hire new people or not. Who to hire, why, and how many. Each new hire is another new obligation (a fixed cost) that increases your risk. How will new people help your business grow and prosper? What exactly are they supposed to be doing? The rationale for hiring should be in your business plan.

- Make asset decisions and asset purchase or lease. Use your business plan to help decide what’s going to happen in the long term, which should be an important input to the classic make vs. buy. How long will this important purchase last in your plan?

More on sharing information

- Onboarding for new hires. Make selected portions of your business plan part of your new employee training.

- Manage business alliances. Use your plan to set targets for new alliances, and selected portions of your plan to communicate with those alliances.

- Lawyers, accountants, consultants. Share selected highlights or your plans with your attorneys and accountants, and, if this is relevant to you, consultants.

- When you want to sell your business. Usually the business plan is a very important part of selling the business. Help buyers understand what you have, what it’s worth and why they want it.

- Valuation of the business for formal transactions related to divorce, inheritance, estate planning and tax issues. Valuation is the term for establishing how much your business is worth. Usually that takes a business plan, as well as a professional with experience. The plan tells the valuation expert what your business is doing, when, why and how much that will cost and how much it will produce.

The standard arguments that apply more to startups

- Create a new business. Use a plan to establish the right steps to starting a new business, including what you need to do, what resources will be required, and what you expect to happen.

- Estimate starting costs. Aside from the general in the point above, there’s the specific estimates that list assets you need to have, and expenses you need to incur, in order to start a new business.

- Seek investment for a business, whether it’s a startup or not. Investors need to see a business plan before they decide whether or not to invest. They’ll expect the plan to cover all the main points.

- Back up a business loan application. Like investors, lenders want to see the plan and will expect the plan to cover the main points.

- Vital for your business pitch and summaries. You can’t really do a good business pitch without knowing already the key parameters you estimate in your business plan, for headcount, starting costs, and of course milestones and key strategy and tactics.

Top 10 Tips for Business Planning

I was asked once again for my 10 top tips on business planning. I can’t do that without noting the different uses of business plans in different situations. I ended up with more than 10 tips, but they are more specific to context.

I was asked once again for my 10 top tips on business planning. I can’t do that without noting the different uses of business plans in different situations. I ended up with more than 10 tips, but they are more specific to context.

5 Major tips for all business planning

- Form follows function. Like anything else in business, a business plan should be judged good or bad not in a vacuum but in its business context with its specific business objective. Most of the online discussion about business plans is focused on business plans related to seeking investment, and I’m going to make the assumption in this answer that you are asking about those. But in real life, the plan related to seeking investment is a subset, a special case. Most real business plans are about managing a business and need a lot less description and research than the business plan related to seeking investment. In most cases, a lean business plan fits the business purpose best.

- Projections are important not for their actual numbers as much as for their presentation of drivers, relationships between growth and spending, key spending priorities, sales aspirations, and assumptions related to cash flow. They have to be solid and integrated, but accuracy is much more a matter of transparent assumptions than accurately predicting the future.

- All business plans should establish strategy, tactics, milestones, tasks, assumptions, and essential numbers (projected sales, direct costs, expenses, and cash flow).

- All business plans should develop accountability and tracking.

- All business plans should be reviewed and revised at least monthly. The review should include looking for changed assumptions and analyzing plan vs actual results with management of the difference.

10 Tips on business plans for seeking investment

- Investors invest in businesses, not plans. The business plan is a necessary but not sufficient condition for finding outside investors. The plan describes the business and what it might become, and that’s all. A beautifully written, edited, and formatted business plan will not make a less investible business more investible. The investment decision is about the content – the team, the market, the differentiators, the scalability, traction so far, validators, growth potential – not the presentation or formatting of the plan. The best use of business plans starts with founders using plans to establish strategy, tactics, milestones, and (especially important) essential projections of sales, spending, headcount, startup costs, capital needs; it’s for the founders to know, first, what they plan to do. Later, as the investment process proceeds (if it does), the latest regularly-revised plan will serve as a companion piece to the pitch and a key document for due diligence.

- You need both pitch and plan. The pitch is a summary of the plan, organized according to highlights for investors, ideally a way to present your business in a structured way. The business plan is the bones of the pitch, like the screenplay, setting strategy, tactics, milestones, market, and essential numbers.

- The normal flow is from introduction, to pitch, to business plan in detail. It’s trendy to say investors don’t read business plans, but what actually happens is they only read business plans of the businesses they are interested in. They reject businesses from intro and pitch, without reading the business plan. The business plan is an essential component of normal due diligence. Never do a pitch without having a plan, because if investors like the pitch they will ask questions that you can’t answer without a real plan. Things like: Could you grow faster with more money? What are your headcount assumptions? How much are you spending on marketing expenses? What are you assuming for payments and collections lags?

- Cover the bases. No need to elaborate here. There are tons of good outlines available, plus books, blogs. Down below I have some specific resources related to my work; but not now. There is no single best outline to use, but investors will want to know about the market, potential growth, competition, differentiation (or secret sauce) strategy, tactics, key milestones, important assumptions, the management team, and financial projections including use of funds, projected sales, income, balance, and cash flow. Use your common sense to put first things first and organize it all well.

- A good summary is essential. Many investors will read only the summary.

- Keep it short. Consider doing just a lean business plan with key info and using your pitch to supplement with more summary and description. Cover the key points and move on.

- It’s about business, not science, not technology. Don’t show off your knowledge. Cover the business essentials including marketing, distribution, pricing, channels, etc.. Leave the science and technology for supplemental documents.

- Forget discounted cash flow, net presented value, IRR, etc. Investors don’t care about uncertainty compounded on uncertainty. They want to know real assumptions that matter. They’ll use their own knowledge and experience to decide about future values.

- Don’t hide anything. It’s not hard to find the key points that investors want you to cover. What’s most important, what order, and how much detail depends on your specifics. Make essential information easy to find. Don’t leave anything obvious out.

- Keep it fresh. That’s why you don’t write a long treatise. A business plan’s shelf life is about a month. Don’t think you can write it once and then live with it for months.

6 Common mistakes to avoid with plans for investors

- Big profits prove nothing but that you don’t know the business. The most common mistake by far is on profits. Startups that grow don’t produce profits. Investors make money on valuation increases, not profits. Real businesses rarely produce more than single-digit profits. Big profit projections are sophomoric. Take all those profits and dump them into marketing expenses and you’ll be better off.

- Prepare to defend hockey-stick projections with believable assumptions and back-up info on how this is realistic. Unsupported huge growth projections are a crock and everybody knows it.

- Being the low-cost provider is very last millennium. Markets split. The low-cost providers are the big dinosaurs with huge capital bases.

- Don’t give all the founders C-level titles. Settle down. Execute, grow, meet milestones, and then up the titles if you haven’t had to bring in some new people.

- Plan to pay your key people. To be honest, some investors like to see founders living on ramen and losing their families. Most don’t. Most investors want you to pay the key people enough to preserve their lives and work ethics, less than true market value, but enough to live on decently.

- Respect normal sales cycles, marketing benchmarks, and cash flow patterns for your industry. For example, if you sell to enterprise it’s going to take a lot of structure, patience, and waiting. If you’re B-to-B then you’re going to need working capital to support receivables. And if you’re industry spends 35% of revenue on marketing, then so do you. Or more, because you want to grow.