In pitches and presentations everywhere, bright young entrepreneur tells cynical skeptical investors, usually with great pride and flourish, about their fabulous IRR for their great new startup. I get a gag reflex.

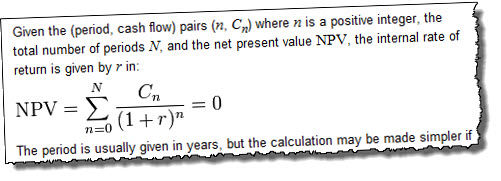

IRR stands for internal rate of return.  You can check wikipedia or investopedia for what that’s supposed to mean and how it’s calculated. It’s supposed to compare cash spent on an investment, over several years, to cash that comes back, which spits out as a percentage. The higher the IRR, the better. They teach it in business schools. It’s kind of an MBA parlor game. It has some very limited usage in comparing past performance of investments, if you can hold all the definitions stable; think of it in a large company context, corporate investments, and corporate budgets.

You can check wikipedia or investopedia for what that’s supposed to mean and how it’s calculated. It’s supposed to compare cash spent on an investment, over several years, to cash that comes back, which spits out as a percentage. The higher the IRR, the better. They teach it in business schools. It’s kind of an MBA parlor game. It has some very limited usage in comparing past performance of investments, if you can hold all the definitions stable; think of it in a large company context, corporate investments, and corporate budgets.

IRR in a business pitch insults my intelligence. It depends on projected sales, costs, expenses, financing, investment, and some hypothetical valuation at some hypothetical time some years in the future. That, by definition, is a crock. Show me the projects, yes. Show me Sales, costs and expenses. Show me cash flow. Go ahead, guess at a future valuation, what the heck. I’ll look at how the assumptions come together and realism, or lack of it, on how the pieces mesh. But the IRR, which summarizing multiple layers of uncertainty as one single percentage number, is totally irrelevant at best, and downright annoying when entrepreneurs act like a projected IRR actually means anything.

And it gets worse, too: there’s the widespread misunderstanding that angel investors and venture capitalists have IRR targets. There’s the unspoken but felt thought: “jeez, what do these investors want? They turned down an IRR of 105%!” And you’ll see people, all over the web, asking what kind of yields they have to give to interest investors. What are the targets?

Talking of IRR if a projected shows me only that you’re too close to the academics. Investors will look at your plan, your team, your product/market fit, and your projections; and they’ll decide what they guess about your future. Stop sooner, before you get to IRR. Let it go.

Comments

which One should I choose, the project with high IRR or Smaller IRR? why?

Smith: You look past the IRR into the assumptions on which it rests, entirely and compare instead the credibility of the assumptions. Choose the one you think is more likely to execute and give you money back from the money you invest. Choose the one with the best product-market mix, defensibility, scalability, and management team. Don’t distract your thinking and judgment by thinking that IRR is a significant number.

BTW, IRR grew up in a world of sophisticated stock analysis and very large corporations, always with the underlying assumption that the underlying factors were relatively equal. That’s so not the case with startups and entrepreneurship, it’s kind of funny that IRR still shows up in business plans for investors. Only because business profs grew up in the age of programmable calculators. I think.

What would you recommend plotting / presenting on the financing slide in a venture pitch then?

Thanks.

-Tim

Tim, re what would I recommend plotting, thanks for asking: I want to see projected sales with key assumptions that drive sales; also projected gross margin, payroll, sales and marketing expenses, and profits.

I don’t take any of these numbers as if they were necessarily going to happen; I take them as the founders’ statement of what they think they can do.

I think the use of IRR in a business plan would just state the obvious for those who actually know what it means in the fist place (what the projections show). I’ve rarely seen it included in a pitch. I haven’t come across investors who are offended by it being presented but at the same time none who would make a decision based on it. Investors will base their decision on their in-depth due-diligence and not on a projection anyway. Best to leave IRR calculations for internal use when putting the business case together for an asset purchase – there it might have some meaning.

Tim:

Enjoyed reading your Blog about IRR. I often questioned it’s misuse.

The following is another reason to question the IRR as explained in wikipedia as follows:

“IRR assumes reinvestment of interim cash flows in projects with equal rates of return (the reinvestment can be the same project or a different project). Therefore, IRR overstates the annual equivalent rate of return for a project whose interim cash flows are reinvested at a rate lower than the calculated IRR. This presents a problem, especially for high IRR projects, since there is frequently not another project available in the interim that can earn the same rate of return as the first project.”

Thanks Milt, that’s a welcome addition, and good to see you here too. Tim