Good advice? In the first few weeks of my first real job, I was heading out to cover a student demonstration in Mexico City when my then boss, the bureau manager of UPI in Mexico City, told me: “Come back with the story, or not at all. If you don’t get the story, don’t tell me the reason why not.”

Bad advice? That’s harder, isn’t it? Don’t you have to be somewhat vindictive to remember bad advice?

More good advice (this one is a quote): “I don’t know the secret to success, but the secret to failure is trying to please everybody.”

And this one, from David Kreps, who taught decision science at the time: “you have to know what knobs you have to turn.”

And Hector Saldana, my favorite client during my middle career in consulting: “90 percent of success is just showing up.” That wasn’t his originally, but he used it often. He also told me once “good management is nothing more or less than knowing when and how to say no.”

Fortune has a feature called The best advice I ever got. Twenty-five well-known people with a picture and a paragraph each. Chairmen and CEOs and celebrities and politicians. There’s a comment area for the rest of us. Here are some quotes from some of them, (unattached from the people, by the way; that seems like a less distracting way to compile advice):

- I’ve observed many CEOs, heads of state, and others in positions of great authority. I’ve noticed that some of the most effective leaders don’t make themselves the center of attention. They are respectful. They listen. This is an appealing personal quality, but it’s also an effective leadership attribute. Their selflessness makes the people around them comfortable. People open up, speak up, contribute. They give those leaders their very best.

- Here is something to remember for the rest of your life: Don’t spend your time on things you can’t control. Instead, spend your time thinking about what you can.

- Always assume positive intent. Whatever anybody says or does, assume positive intent. You will be amazed at how your whole approach to a person or problem becomes very different. When you assume negative intent, you’re angry. If you take away that anger and assume positive intent, you will be amazed. Your emotional quotient goes up because you are no longer almost random in your response. You don’t get defensive. You don’t scream. You are trying to understand and listen because at your basic core you are saying, “Maybe they are saying something to me that I’m not hearing.” So “assume positive intent” has been a huge piece of advice for me.

- If you have something good to say, say it in writing. If you have something bad to say, you should tell the person to his or her face.

As soon as I saw it I started musing about bad advice. What was the worst advice you ever got? That would also seem interesting to me. And then, lo and behold, one woman included did in fact go for the worst advice instead of the best advice. Here’s what she said:

The worst advice I ever got was, “Don’t work with your husband [Pan Shiyi]. Marriage and business don’t mix.” You can’t imagine how many people told me this. But it’s such a narrow view of relationships. In our case I think our [real estate] business success springs from our friendship.

When you have two people trying to figure out problems together, one brings out new things in the other and vice versa. Aren’t human beings meant to be inspired in this way? With us, Pan works in a very intuitive way–even though he’s the man. I believe in women’s intuition, but I am also a product of my Western training [Cambridge, Goldman Sachs]. And so we approach decisions in very different ways and play different roles. He tends to come up with big ideas–then I’m the one who goes around trying to test them. He’s brilliant at sales. I worry about construction.

If the business fails, well, that puts a strain on the marriage. But what if it succeeds? That can enhance the marriage. When it comes to business and relationships, I don’t buy this idea of diversification. It neglects comparative advantage. The best way to lower risk is to specialize: Put the things that you love into one portfolio.

What about you? Could you name the best advice you ever got? How about the best you ever listened to? The worst advice?

You Have to Know When to Quit

I recommend you read Nat Eliason‘s piece No More Struggle Porn. He’s attacking one of the more pervasive startup myths around, the idea that the struggle itself, the overwhelming and overpowering struggle that pushes everything else out of your life, is a good thing. He defines struggle porn as:

I recommend you read Nat Eliason‘s piece No More Struggle Porn. He’s attacking one of the more pervasive startup myths around, the idea that the struggle itself, the overwhelming and overpowering struggle that pushes everything else out of your life, is a good thing. He defines struggle porn as:

I call this “struggle porn”: a masochistic obsession with pushing yourself harder, listening to people tell you to work harder, and broadcasting how hard you’re working.

And his take on it, in a nutshell, is this:

Working hard is great, but struggle porn has a dangerous side effect: not quitting. When you believe the normal state of affairs is to feel like you’re struggling to make progress, you’ll be less likely to quit something that isn’t going anywhere.

The Myth of Persistence

I agree with him. Emphatically. I’ve posted here before on The Myth of Persistence:

Why: persistence is only relevant if the rest of it is right. There’s no virtue to persistence when it means running your head into walls forever. Before you worry about persistence, that startup has to have some real value to offer, something that people want to buy, something they want or need. And it has to get the offer to enough people. It has to survive competition. It has to know when to stick to consistency, and when to pivot.

So persistence is simply what’s left over when all the other reasons for failure have been ruled out.

Knowing When to Quit

And, with that in mind, I like Seth Godin’s take on quitting, which is the main point from his book The Dip (quoting here from Wikipedia🙂

Godin introduces the book with a quote from Vince Lombardi: “Quitters never win and winners never quit.” He follows this with “Bad advice. Winners quit all the time. They just quit the right stuff at the right time.”

Godin first makes the assertion that “being the best in the world is seriously underrated,” although he defines the term ‘best’ as “best for them based on what they believe and what they know,” and ‘world’ as “the world they have access to.” He supports this by illustrating that vanilla ice cream is almost four times as popular as the next-most popular ice cream, further stating that this is seen in Zipf’s Law. Godin’s central thesis is that in order to be the best in the world, one must quit the wrong stuff and stick with the right stuff. In illustrating this, Godin introduces several curves: ‘the dip,’ ‘the cul-de-sac,’ and ‘the cliff.’ Godin gives examples of the dip, ways to recognize when an apparent dip is really a cul-de-sac, and presents strategies of when to quit, amongst other things.

Don’t let the struggle porn startup myths get you down. I’ve been through startups. I’ve been vendor and consultant to startups for four decades, and I started my own and built it past $9 million annual sales, profitability, and cash flow positive, without outside investors. And I’ve never believed that anybody is supposed to give up life, family, relationships, and the future to build that startup with 100-hour weeks and forget-everything-else obsession. Here’s what I say:

Don’t give up your life to make your business better. Build your business to make your life better.

Angel Investment Red Flags

Last week at an angel investment meeting one of our group members asked whether anybody had a list of red flag problems that would immediately eliminate a startup from consideration by angel investors. That seemed like a good idea to me then. And over the weekend somebody asked a similar question in Quora: what are some red flags for people new to angel investment when evaluating companies.

This blog post is a compilation of my own items and a lot of others contributed to the Quora question.

My big two:

- Issues around trust or integrity. Alternative truths don’t fly. Lies, gross exaggerations, hiding significant information. Fudging past financial data. Not mentioning about or grossly exaggerating their previous business history. Omitting significant facts. the pitch brags about a founder’s previous successful exits that turn out, later, to have been either grossly exaggerated. Founders holding back critical information for problems of perceived confidentiality or trust. Lawsuits that weren’t mentioned. Cap tables that hide things. Gaps in the history.

- Issues around Leadership. For example, the scientist alone, instead of the scientist in a team with experience in the industry and business sense and experience. Or the team that lacks the CEO and is promising to get one after funding. Or the team of very young people that assigns all C-level positions to team members without realizing they need somebody else.

Four other good ones from Heather Wilde.

- Lack of domain expertise – Anyone can have an idea, but if the person you’re considering has no clue about what’s possible, what’s been done before, or even a tangentially related background – that’s a huge red flag.

- Lack of Coachability – there’s a certain amount of arrogance expected in an entrepreneur (they need to beat down their competition), but if they aren’t willing to consider outside advice or suggestions, stay away.

- Terrible Idea – I shouldn’t need to say this, but the majority of ideas are actually just bad, really, really bad. Yes, you are investing in the human, but that doesn’t mean you should throw money at a bad idea in the hopes that something they come up with later might be good.

- “No Competition” – This is like one of those logic puzzles. Every time I hear someone say “we have no competition” it immediately is a red flag, for two reasons. One, it’s a sign they haven’t done their research, because there’s always competition, or at least something comparable. Two, it’s a sign they might be naive enough to actually think it’s true. Either way it’s a sign to stay away.

Four more from Greg Brown:

- Awesome team in a small market can figure out how to expand the market opportunity. Mediocre team in a brilliant market will produce mediocrity. Bet on the team.

- Legal and financing structures that violate the norms are non-starters for me. No need to reinvent the wheel.

- If a company is pushing too hard to get your investment that’s a bad sign. If it doesn’t yet feel right hold off. It’s OK to miss out on something. There will be other opportunities. You cannot ride every unicorn.

- Bad co-investors suck. Bad means fundamentally bad people or people who will provide bad advice or influence. Most founders will to some degree bend to the will of their board/investors. Make sure they will be getting good advice.

And a bunch from Terrence Wang

- No Deck/No Financial Model. Sending decks are standard unless you are a Siri co-founder working on Viv. VCs want financial models. If you are investing later seed then the startup should send you a financial model where you can see the assumptions and play around with the variables to test different scenarios and outcomes. If founders won’t send you both, red flag.

- Finders/Brokers/Enthusiasts. At present the vast majority of finders, brokers and enthusiasts who connect founders and investors are working with non-great founders. Red flag.

- Super Angel or VC Advising, Not Investing. Peter Thiel is advising a PayPay mafia cofounder-CEO. The CEO pitches fellow angel investors and me. We ask if Peter is investing. The CEO says he wants to be careful about asking Peter to invest. So why are you pitching us then? Red flag.

- Product Not Needed. If someone loves a startup’s product and service, that could be because the product is free and a good time filler. Doesn’t mean they will spend money on the product or service. Maybe they don’t need the product. Red flag.

- Not Great Sales. A great product with bad sales is often a bad sign. For example, a startup might have a great e-commerce product but Amazon is going to out-sell them about a billion to one. If the product is easily monetizable and they haven’t even tested monetization, that is a red flag.

- Incompatible Goals. Some angel investors don’t want VCs involved later. This includes at least a couple Harvard Business School Angels who invest in startups that should not need VC funding because the startup is in a smaller market and should get to break-even pretty quickly. But does the founder agree? If you and the founder don’t agree on the financing goals, that is a red flag.

- No Grit. If the CEO does not have grit, the startup likely won’t work. Red flag.

- Uncompelling Pitch. CEOs need to be persuasive, regardless of context. They don’t have to be high energy. Elon is more reserved but still charismatic and persuasive. Uncompelling pitches are a red flag.

- Differing Visions Intra-Team. Talk to the CEO and other core team members individually. Are they on the same page as the CEO? If not, red flag.

- Can’t Lead. Has the CEO built and led a team successfully before in anything? Sports, clubs, etc.? Her siblings? Anything? If not, red flag.

- Unanswered Questions. If you have unanswered questions that are important to you about anything related to the startup, the team, the legal documents, etc., make sure the CEO or someone from her team who’s authorized (e.g., her law firm) answers your questions to your satisfaction. If you feel pressure to not ask too many questions, just ask this one

- Legal and Ethical Issues. Does the CEO do things that are highly unethical or technically crimes? If so, you may have a Theranos or Zenefits on your hands. Red flag.

Rant: Entrepreneurship, Dropouts, and Bad PR

I was writing an email to these folks and I just stopped and deleted the draft. Why waste the time raising entrepreneurs I don’t even know.

I was writing an email to these folks and I just stopped and deleted the draft. Why waste the time raising entrepreneurs I don’t even know.

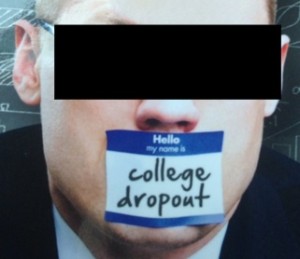

My complaint? I got to my office this morning after a few weeks elsewhere and found the results of a concentrated campaign for me to write about a certain entrepreneur and his startup. He’s all about how he’s so successful as a college dropout. I have one package containing a coffee mug with chocolate drops, and another with a copy of his book. Both contain a personalized letter from him, with what looks like a signature. Both contain business cards that are ‘sort of’ from him, but not exactly. And the only contact info I get is an impersonal email address info@[company omitted].

So, let’s get this straight: You want me to write about you, but you don’t even give me your email address? Is that just me, or is it insulting?

I connected this to multiple emails from somebody in his company, pitching me talking to him or interviewing him, also without including his email address. I’d say WTF, but I’m more mild mannered than that, so only WTH.

Besides, the college dropout theme ticks me off. The illustration here is taken from the cover of his self-published book. And the email campaign spins off the college dropout thing. I think that’s building your image around what’s essentially bad advice.

One thing is all the reasons like you or the next person or anybody else had to drop out of college — too bad, but common enough, and nothing for me to judge — but quite another is purposely building your entrepreneurship pitch around you having dropped out of college. Yeah, sure, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg, I know. But none of them ever made that his secret sauce; the college dropout thing just happened. Bill Gates regrets dropping out of college. Steve Jobs hung around Reed College for the education, even after he dropped out. And Zuckerberg? OK he had a tiger by the tail, who can blame him? But does he go around bragging about it?

Sadly, formal education becomes a luxury for some. I wish it were available for all. But I’m sure anybody who can get an education is better off with it than without it. And that goes for entrepreneurs too. No, you don’t learn to be an entrepreneur in courses. But what you do learn doesn’t hurt. And there’s a whole life outside of business.

Obvious Trite Advice is Just More Clutter

I just read Five Pieces of Blogging Advice I Wish You’d Stop Giving on problogservice. How about this one? Post author Erik Deckers writes, as his number one piece of bad advice:

Write good content: Blah, blah, blah! People say this like it’s The Most Important Advice Ever. It’s stupid, vile, and utterly useless, because everyone a) knows it, and b) thinks they do it.

The comments there are Erik’s not mine, but I agree completely.

Obvious advice is just clutter. And it interferes with useful advice.

Here’s another one:

Grow your social network: Really? I thought having my brother and a couple friends from work following me on a Twitter account I rarely use was a guaranteed step toward social media rock stardom.

Yep. More obvious and trite advice. Point taken. And this one:

Find your niche/passion: Okay, this one might not be such a Duh! piece of advice, but I’m tired of it. Anyone who has a barely detectable pulse has heard this one before, so it’s nothing new. Combine this with item #1 — write passionately about your content — and Tony Robbins will personally punch you in the nose.

Erik goes on and the post stays good. I agree.

Good Advice Often Makes Bad Things Happen

Mike Myatt, who writes on leadership, says it straight. In a post titled Really Bad Advice, he first sets the scene:

I just finished reading an article where the author (a self professed innovation guru) recommended strategy be aligned with capability, and that to allow ambition to exceed capability is a nothing short of a recipe for disaster.

And then he tears into that:

Let me get right to it – if you want to fail as a leader then please follow the flawed advice given by the wizard of innovation mentioned in the opening paragraph. But if you want to rise above the crowd and become a truly innovative leader, I’d ask you to regard said advice for what it is – more of the same. It’s just another well-intentioned sound bite that will destroy your company and your career if you choose to follow it.

The underlying problem, much more general than Mike’s specific issue, is quite common: Good advice makes bad things happen. Business, like life itself, is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Every case is different. What worked for me could easily be disastrous for you. I’m flattered when people ask my advice, but I’m always hoping they have the common sense to listen, digest, evaluate my story for their situation, and execute on it only if it actually makes sense for them, then, in their situation. I shudder when it seems like people are going to just execute on my advice without internalizing first.

Meanwhile, back with the specific issue on strategy, Mike puts his objection very clearly:

leaders who complain about a lack of resources, are simply communicating they are not very resourceful. Great leaders find a way to develop and/or acquire the best capability in order to create a certainty of execution around a winning strategy. If you want to fail as a leader, hire B and C talent and ask them to win with an inferior strategy. Thinking in a limited manner will only accomplish one thing – it will limit your future.

That too, I think, is good advice that might or might not apply to some other situation. To be taken in moderation, and used with care.

Conclusion: This goes straight to my general feeling that there are no such things as best practices.

(Image: bigstockphoto.com)

12 Ways Best Blogging Practices Aren’t

I like Blogger Brad Shorr‘s list of 12 Most Horrible Pieces of Blogging Advice (no longer available online). It’s a good list, well worth reading, good food for thought. More important, in my opinion, is that it’s also an eloquent reminder of the essential case-by-case rule that applies not only to business blogging but also to all of small business, beyond blogging.

Here’s Brad’s list of 12 pieces of bad advice:

- Keep posts under 300 words

- Stick to a rigid publishing schedule

- Blogs are an SEO shortcut

- Bloggers need to be edgy

- Images aren’t important

- Blogs should be monetized

- All it takes to succeed is quality content

- Cultivate reciprocal links

- You must use a custom design

- Blogging has been replaced by social media

- Corporate blog content can be outsourced

- It’s all about subscribers.

In most of these cases, Brad takes a commonly accepted best practice or general rule and points out the exceptions. He sums up most of this with his very first item, for which he explains:

Beware of absolutes. This advice stems from the generalization that all blog readers are in a hurry. However, if your blog’s purpose is to provide information or analysis, and you’re good at it, people will be willing to read five times that word count.

In other cases, advice that used to be good advice has gone stale. For his #8, on reciprocal links, he explains:

This is an outdated SEO tactic that can now do more harm than good if you have links coming in from bad sources. For audience building only, reciprocal linking is OK, but only when you are selective in terms of the relevance and quality of your link partners.

And that, aside from blogging specifics, is the real nugget in this particular post. Attractive as advice and guidelines are, out here in the real world everything is case by case. The only rule is that there are no rules. Best practices only work when applied carefully with a lot of respect for the specifics of context and a lot of flexibility to use not as directed.

I’m sure that applies for small business too, not just blogging. And maybe for life in general too? What do you think?

No, 37signals, Planning Is NOT What You Think

Rich irony: 37signals, publisher of Basecamp, the leading web app for project management, ought to know better than anybody that real business planning is a process, not a plan. After all, they do the kind of nuts and bolts management that makes that happen. Instead, however, Matt of 37signals posted the planning fallacy last week:

If you believe 100% in some big upfront advance plan, you’re just lying to yourself.

I object. Who ever said planning was “believing 100% in some big upfront plan?” Good business planning is always a process involving metrics, following up, setting steps, reviewing results, and course correction.

He goes on:

But it,s not just huge organizations and the government that mess up planning. Everyone does. It’s the planning fallacy. We think we can plan, but we can’t. Studies show it doesn’t matter whether you ask people for their realistic best guess or a hoped-for best case scenario. Either way, they give you the best case scenario.

OK that’s a dream, not a plan. Matt seems to confuse the two, but good business planners don’t. Any decent business planning process considers the worst case, risks, and contingencies; and then tracks results and follows up to make course corrections.

Which leads to this, another quote:

It’s true on a big scale and it’s true on a small scale too. We just aren’t good at being realistic. We envision everything going exactly as planned. We never factor in unexpected illnesses, hard drive failures, or other Murphy’s Law-type stuff.

No, but you do allow extra time for the unexpected, and then you follow up, carefully (maybe even using 37 Signals’ software) to check for plan vs. actual results, changes in schedule, new assumptions, and the constant course correction. Murphy was a planner. He understood planning process, plan review, course corrections.

Matt concludes:

That messy planning stage that delays things and prevents you from getting real is, in large part, a waste of time. So skip it. If you really want to know how much time/resources a project will take, start doing it.

Really bad advice there, based on a bad premise. Sure, if you define planning as messy and preventing you from getting real, then it would be a waste of time. But is that planning?

I wonder if Matt takes his own advice. When he travels, does he book flights and hotels? Or does he skip that, and just start walking.

The One-Page Resume Discussion

Business Pundit has this post by Robert May about resumes today …

“According to this graphic from the Journal of Accountancy, resumes with 2 or 3 pages are fine for executive level candidates. I always heard you should keep it to one page no matter what. Apparently that was bad advice…. ” Read more

I’m with you, Rob. One page is plenty. I’ve never met a person whose resume needed more than one page.

The more you’ve done, the more compelling the summary, the more powerful the dignified understatement. Did Shakespeare have to list every play written? Does Jay Leno list every appearance? Even the president of the U.S. should keep it to a single page: President, Governor, Harvard MBA, etc.

The resume is just a foot forward. It’s for a gatekeeper to decide on the next step, or not take it. Think of how much fun you’ll have embellishing during the interview.

Stanford University required 1-page resumes, without exception, when I got my MBA 25 years ago. I hope they still do.

–Tim